The early days of the Port Kembla steelworks saw the involvement of people of a wide range of backgrounds and aptitudes. They were building the infant industry under often trying circumstances, when even the national economy itself was in a very poor state. The success of their endeavours is reflected in what they built up and left for the future, in both tangible and less tangible form. One who exemplifies that is described here – a person who joined the company in its earliest days as a Swiss trained engineer, and who ultimately left the company to form his own engineering business. He left behind both business practices and physical equipment of singular importance to the efficient and effective use of energy. Those practices were to become even more important in modern times than they were when founded. The person was Hans von Escher (in Australia generally Hans Escher) – engineer, inventor, musician, film-maker, proficient linguist (speaking five languages) and inveterate traveller.

Hans Escher was born in Cairo on March 3, 1906 to parents from one of the oldest Swiss families, Henri von Escher and his wife Fortunie. (There is some conflict in records as to whether he was born in Cairo or Zurich. Henri von Escher was reportedly for a time in Egypt in a diplomatic post and Hans lived there until his youth – a factor, he noted later, in developing his interest in engineering, through looking at the simple water pumping systems used in Egypt for irrigation.) He went to Switzerland for technical education, and graduated in mechanical engineering from the Zurich Institute of Technology (now the well-known ETH Zurich).

Following graduation in 1926 he worked at Escher-Wyss-Cie on the design and testing of turbine blades and centrifugal pumps. He left Switzerland for Australia in 1927, arriving in Sydney on the SS Moldavia in August. There he joined Hoskins Iron and Steel at their Sydney operation in the design area, moving later to their under-construction steelworks at Port Kembla, working on the erection and blowing-in of the No 1 Blast Furnace. Thus he was part of Hoskins Iron and Steel in its formative days. His principal interest then and later lay in thermal engineering, a core component of steel plant design and operation. He was particularly engaged with furnaces – boiler furnaces, and the various heating furnaces which were part of steelmaking and steel processing. The efficient use of energy was a central guiding principle – an issue which has if anything gained even more importance since then, carrying with it now, as it does, major connotations because of climate change-forcing through fossil energy use.

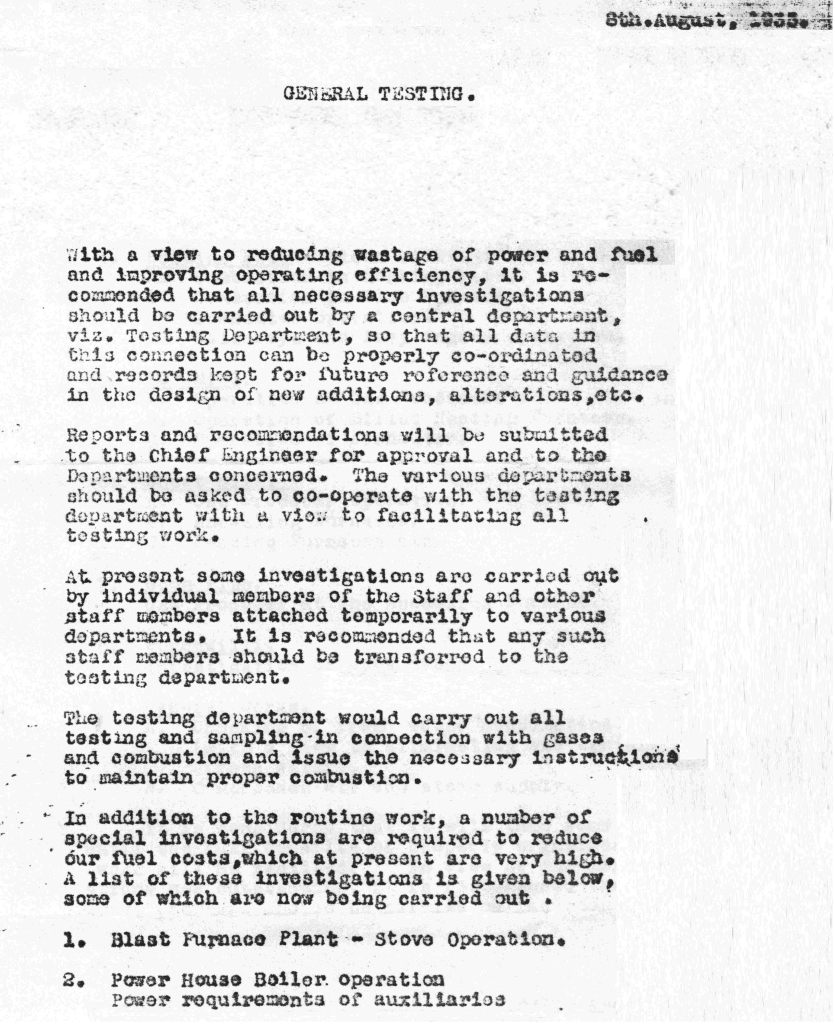

It was a difficult time for the new steel company in the late 1920s and 1930s. Escher’s early focus was on the efficient operation of existing equipment. He recognized that with the financial limitations of the time, the main area for cost reduction was through their existing equipment. His examination of existing practices suggested there was indeed much to be gained from their more efficient operation, and he argued for a more clearly defined focus on that operation. He later wrote (as part of an approach to plant management) a prescription for what amounted to an ‘efficiency department’ – a Testing Department as he called it, defining a formal organizational approach to energy conservation. The letter was written nearly ninety years ago, and embodied concepts from other management streams – the concept, for example, that “…if you can’t measure it, you can’t control it”. His suggestions clearly resonated with management of the time, and the department he suggested was indeed formed, not under his suggested name, but rather as the ‘Combustion Department’, a group which remained as that for over sixty years. (The draft of his letter is shown below.) He was in fact the first Chief Combustion Engineer. The work Escher did was not all hands-on plant work. For example, he took a strong interest in plant design (as later reflected in his various patents). In 1939 he was awarded a prize (the Ablett Prize) by the Iron and Steel Institute (UK) for a paper titled “Ten Years Development in Steam Engineering at the Port Kembla Steel Works, N.S.W., Australia” (Nature 143, 851 (1939)).

Hans Escher Letter 1935: Recommends ‘Testing Department’

Hans Escher looked not only at optimizing current equipment operation, but also at ways in which the equipment itself could be improved for higher energy efficiency (and hence lower product cost). He focused particularly on energy recovery – gathering the ‘waste’ heat energy being discharged from a heating operation and using it to pre-heat cold combustion air for the process. Results showed that up to 20-25% of input energy might be saved through the use of equipment designed for that purpose (‘recuperators’), which was a very major saving. In an operation such as a steel plant, with numerous heating furnaces associated with rolling operations, the potential for gain from energy saving through such devices is significant. A typical application for such equipment would be on a reheat furnace heating steel slabs prior to their being rolled in a plate mill.

Image courtesy Fives Group

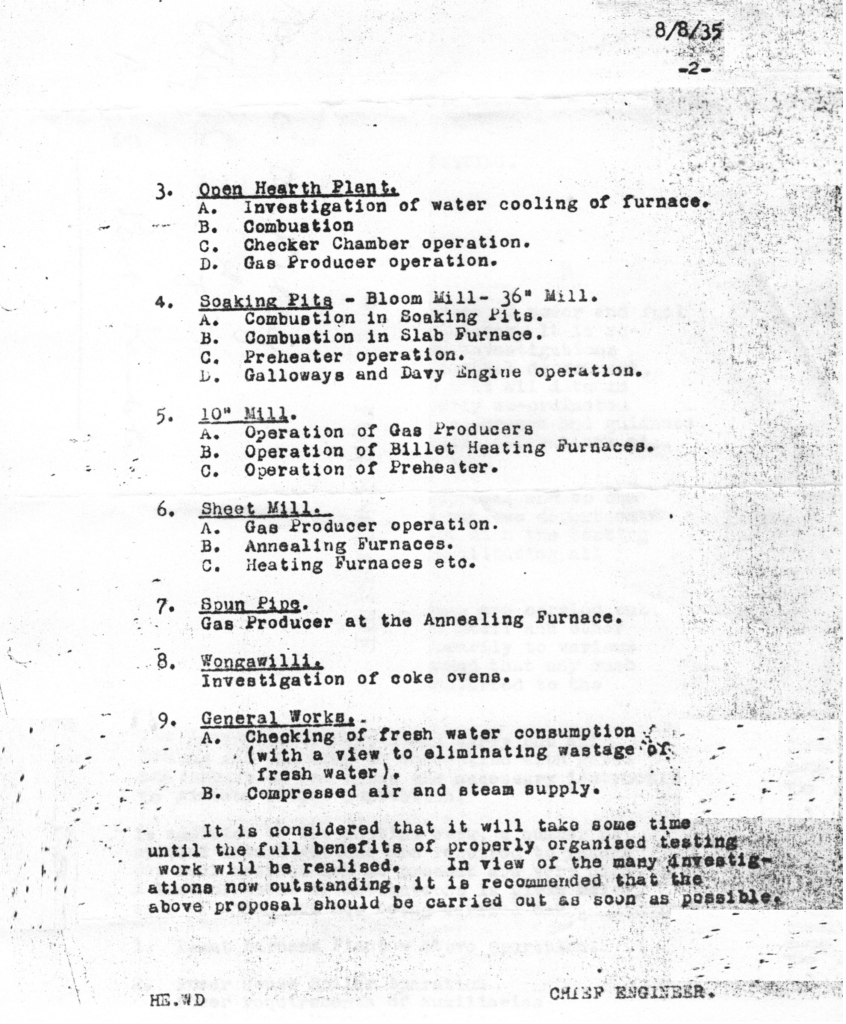

Hans Escher eventually had some ten patents to his name, several shared with Australian Iron & Steel where he worked in developing the equipment concerned. Escher held various international patents as well as Australian patents, the most important patents being for recuperator designs. Recuperators of his design were used in a number of countries, and remain a standard piece of equipment for furnaces of various types.

It was in fact to the business of recuperator development to which he moved when he left Australian Iron and Steel in 1952, setting up his own firm to design and manufacture recuperators for furnaces of various types. What is now known as the ‘Escher recuperator’ continues to be applied to service furnaces of various types over seventy years later.

The illustration here from one of his early patents shows the simple yet robust design, which has changed little over the years.

An example of a recuperator fabricated in Wollongong in 1967 for use in the US may be seen in this archival footage https://archivesonline.uow.edu.au/nodes/view/12372 . The unit shown was being shipped through Port Kembla for an industrial application in the United States.

An illustration of current US manufacture, at impressive facilities in Toledo, Ohio may be seen below. It is a tribute to the aptness of the recuperator concept that it is still known (and by its creator’s name) and in current use more than seventy years after its development.

Image courtesy Maumee Valley Fabricators, Toledo, Ohio

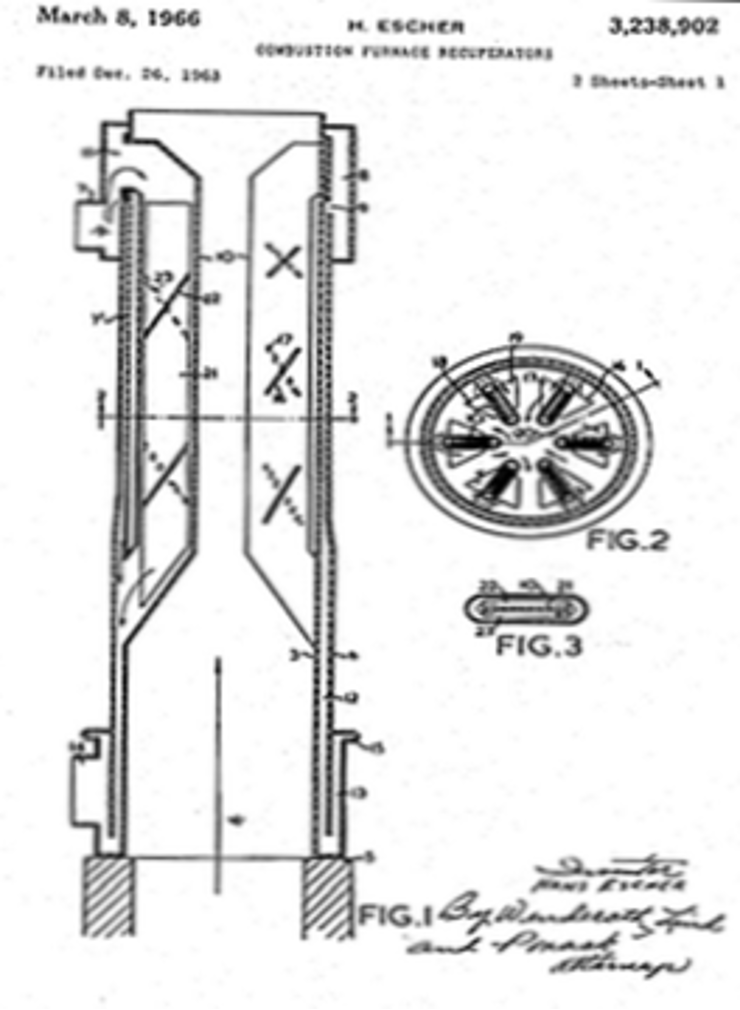

https://maumeevalleyfab.com/services/escher-division/

The onset of World War II in 1939 placed Escher in an ambiguous position – while not able to actually work in the steel plant (being classified as an alien for his Swiss origin) he was nonetheless able to freely access the plant. He proceeded to utilise his film-making talent to produce a colour film of operations at the steel plant, with some background from the local area generally. The film was silent, but in its numerous public presentations were commonly accompanied by a scripted verbal commentary. The film may be seen on the National Film and Sound Archives website here. It was often the basis of benefit public showings particularly in the 1940s. Also popular were the ‘travelogue’ films he produced from their various international travels with his wife Hilda. Conversely they also widely showed films of Australian aspects when travelling overseas.

Another aspect reflecting his ever-present fascination with things technical was his development of a gas-powered motorcar during the serious fuel-shortage days in Australia during World War II. At that time, much of Australia’s transport fuels were being imported, with consequent major risk. This was achieved by equipping a small Austin car with a ‘gas-bag’, which was then filled with towns gas (at that time produced by coal-fired gasifiers). The vehicle was somewhat unmistakable.

The December 1941 BHP Review reported that “The gas bag holds 110 cu. ft., and gives a range of 16 miles. A speed of 40 miles can be maintained normally, but with strong head-winds this has to be reduced to 30 miles per hour.” Separately, a works utility was fitted with a gas producer, a device for producing combustible gas from a coal feed.

So the person described here was well ahead of his time in at least two facets of industry still of major importance – the issue and the practice of active energy management at all levels, and one major means (energy recuperation) by which that may be achieved for furnace plant. But there were two other aspects to this large character: his love for and ability in singing (and in music generally), and with his pursuit of travel and touring, as noted above a passion for photography and filming.

Hans Escher was an accomplished bass baritone, with a leaning towards Verdi, but with a broad repertoire. His wife was the former Hilda Boyle, a well-known contralto on Australian radio in the 1930s and later. Both separately and together they performed many times at various types of musical functions in both Wollongong and Sydney, from small musicians’ gatherings, through to full public concerts. As a part of that, they were well-known in musical circles generally, and credited (with others) with establishing a broad and well-patronised musical scene in Wollongong, bringing well-known Australian musicians such as Percy Grainger to perform in their home. They remained also a part of the broader Sydney musical scene, in both concert performances and musicales – those smaller gatherings in private homes. Music – both their own and that of others – was a major feature of their lives.

via Trove

The Eschers were enthusiastic travellers, and their tours were often long – one of their major tours being around two years overall. But they were not mere sightseers – Hans was an inveterate photographer and film-maker, and the extensive body of travel film footage they developed formed the basis for many (very popular) film shows on their return. In 1931 Hans had left Australia for a tour of some two years, principally to Japan and the US, where in fact he married Hilda Boyle in September 1931 in Los Angeles. They then travelled further before returning to Australia. Over the years, among other places they visited Britain, Japan, the United States, Switzerland, Canada and New Zealand, all the while making travel film documentaries for later showing. The large body of travel film documentaries which they created were popular in numerous charity film showings in Wollongong over the years.

In 1952, immediately after leaving Australian Iron and Steel, Hans and Hilda Escher left on another extended trip to the UK, Europe and the US. (The latter was notable for the fact that they purchased a small car in Britain (a Moris Minor) in which while touring they drove 14,000 miles (over 22,000 km) around the USA: a formidable trip indeed!)

A demonstration of the regard in which Australian Iron & Steel held Hans Escher was the fact that prior to his departure in 1952, he was the guest at two large farewells – one from his own (Combustion) department, another at the Company’s executive guest house by the senior management of AIS. He had left a legacy of practice and equipment in the pursuit of energy conservation which was to last for some decades – and which is particularly relevant today to efforts to reduce the impact of fossil fuel use on the Earth’s atmosphere.

Hans Escher moved on to establish his own company and successfully pursue the adoption of energy recovery technology in Australia and elsewhere. He died in Sydney at the age of 78 in 1985, his wife Hilda having predeceased him in 1958. The pursuit of energy efficiency is now, once again, firmly established as an important avenue to greenhouse gas reduction. Forty years after his death, the Escher recuperator remains a standard approach to such energy recovery in various industries, a testimony to his commitment to energy saving, technical capability, and capacity for innovation.